In Totnes, the transition in the heart of the city<

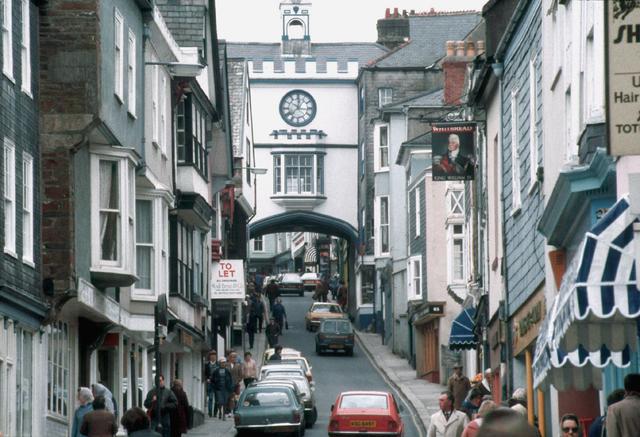

Totnes, a town of 8,000 inhabitants in Devon, in the south-west of England, seems preserved in formaldehyde. Its main street might not have changed in decades. Its three butchers offer appetizing lamb chops and Scottish Eggs (soft-boiled eggs surrounded by sausage meat), a miracle in a country where meat stalls are often only found in supermarkets. The exterior walls of several of their neighboring buildings still display their ancestral tiles, a tradition of the region. The candies at Cranch's are probably the same ones the cashier's grandmother tasted in secret. Under its very conservative appearances, Totnes nevertheless wants to be the pioneer city in terms of transition. Through community projects, this model aims to increase self-sufficiency to face the future scarcity of oil, to limit climate change and economic instability.

Practices brought together in a single movement

At the origin of the concept of the city in transition, now taken up in hundreds of cities around the world, the permaculture activist and teacher Rob Hopkins. “Rob chose to settle here in 2006 because of the already existing cultural ground”, assures Wendy Stayte, 80 years old, 28 of whom spent in Totnes, involved from the start and still very active. “The city was already somewhat famous for its alternative way of life. In their corner, some of its inhabitants sought to change their relationship to life, whether in agriculture, construction or art. Rob's contribution was considerable: he brought all these practices together in one movement. This experience attracted many people from outside. »

In the early years, the actions of the “transitionists” were very visible. Behind the station, Briony Baxter, 62, is busy in the five common gardens of the city, gathered under the name of Incredible Edible (incredible edible). There are currently growing green beans attacked by slugs, fennel and lettuce, in addition to many varieties of aromatic herbs and an apple tree. As for strawberries, they gave way to raspberries. Everyone is free to use. "I grew up in a very poor area in the north of England and as a child I knew hunger," recalls the head of the gardens. It was already not normal at the time but that in 2020 millions of people are forced to go to food banks for food is even more shocking. »

At his side, Jenny, 31, came to help him clear the brush. “I moved here a short time ago and I had heard of Totnes in the French film Demain, says this marine environment student. I had never planted anything before confinement: with my family we grew wild flowers in a large empty space behind our house to feed bees and birds. I want to do the same here. »

Over the years, the projects have become more complex. No doubt partly due to contact with the neighboring Schumacher College, renowned for its courses on the environment and its critical thinking. Most of its students and teachers turn out of class into activists, and feed as much as possible the theoretical reflection of local residents. “We emphasize economics because most of our students, like activists, often see their ecological dreams shattered by the need for them to make economic sense,” says Jonathan Dawson, the course coordinator. economy of the establishment.

Involvement at all levels

So much so that the Totnes Transition Town banner now brings together social projects for the homeless and drug addicts, as educational support programs in poor neighborhoods or even the construction of housing and offices at really affordable prices on a fallow site. “In some files, we put ourselves forward, in others we make the link between different entities, whether private or public, specifies Luciana Edwards, 31 years old. For example, in agreement with the municipality, we worked with a property developer to create a pedestrian path from his development to the nearby park, organize cycling lessons for locals, etc. »

The municipality is also fully involved in the transition project: it officially adopted it in 2009. In December 2018, the municipal council declared a climate emergency and announced its desire to reduce the Totnes CO2 emissions from 2030.

The evolution of the initial project and the integration of its ideas into all spheres of Totnes society are the mark of its success. A success not flashy but, in view of the attraction of this city lost in the depths of England, certainly undeniable.

The difficulty of integrating historic residents

Each year, many observers travel to Totnes to study their transition pattern. For several days, sometimes several months, they observe closely the concrete meaning of these ideas that are now fashionable. However, not everyone in the city feels concerned by the initiatives of Transition Town Totnes (TTT). “Projects like Caring Town Totnes, for the homeless and drug addicts, are very well received by the general population,” explains Luciana Edwards. On the other hand, certain projects, such as our support in 2012 for the campaign opposing the installation of a Costa chain store, made us pass for arrogant people, giving lessons to certain locals…”

The case began in May 2012 when this British coffee giant applied for a location in the main shopping street. Very quickly, a petition was launched. It calls for preserving the local economy, composed mainly of independent businesses, and therefore to oppose its installation. TTT chooses to support it. The petition is finally signed by 5,750 people. During October, the boss of Costa canceled the opening of the store following a visit to the city. In his letter, he points out that “Costa recognized the strength of sentiment against national brands and took into account the specific circumstances of Totnes”.

While half the city is jubilant, the other half is gloomy. TTT is taken as a scapegoat. A Take Back Totnes Facebook page is being created “for anyone opposed to the narrow minds of Totnes Transition Town who seem determined to keep Totnes stone-age”. As a defense, TTT defends itself from promoting short circuits, which above all benefit local traders and therefore the city, rather than distant shareholders.

Reaching all social strata

This episode gave rise to the desire to get the transition out of its rut. Even if eight years later, the path still seems long. “It is difficult to attract new or different people, regrets Luciana Edwards. Even today, when we distribute leaflets to encourage people to come and pick fruit in our gardens in Bridgetown, the poor district of the city, we mainly see people who are a little well-off come. As if the locals were thinking, 'This kind of event is not for me.'”

The young woman is currently working on a project aimed at reaching out more to their contacts in order to break the glass wall that separates them. There is no doubt that their involvement in TTT would mark its most convincing success, and would at the same time ensure its sustainability.

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev