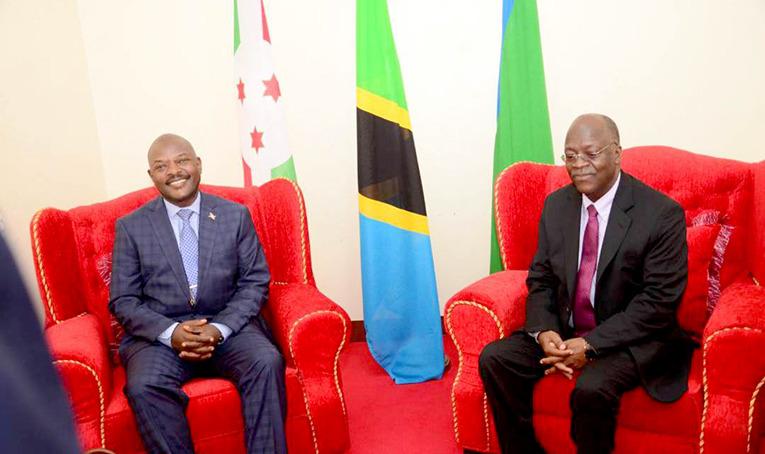

The key to peace in Burundi is in Tanzania<

At some point, it is likely that the actors involved in the bloody political crisis in Burundi will meet around a table in Arusha, Tanzania, to find a political agreement.

Arusha, a cosmopolitan and laid-back city in northern Tanzania, is the traditional venue for negotiations to settle some of the most difficult conflicts in East Africa. It was in Arusha that the Burundian government and CNARED [National Council for the Respect of the Arusha Accord and the Rule of Law in Burundi], the opposition platform, were to meet last week to participate in the negotiations framed by the African Union (AU) and the East African Community (EAC), but the government withdrew its representatives from the negotiation process on the grounds that they could not meet "criminals" and " terrorists”.

Read: Briefing: What will be the next steps in the peace process in Burundi? These setbacks are nothing new. After all, the purpose of mediation is to bring people who hate each other together, sometimes with murderous intensity. It took a year to negotiate the Arusha accord that ended the Rwandan civil war; the process of negotiating the Arusha Accord for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi (the document that the current government allegedly sabotaged, according to CNARED) lasted two years.

And when it comes to South Sudan, who knows how long it took to negotiate the peace accord signed last year in Arusha before it was promptly rejected by both sides?

Why Arusha? Arusha is a tad schizophrenic. It attracts hordes of tourists eager to visit the Serengeti National Park, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area and Mount Kilimanjaro. But in addition to backpackers in sandals and camouflage outfits (they are rarely dressed like this), it welcomes men and women in suits and suits who represent the other face of Arusha, that of the regional diplomatic crossroads.

It is in this city that the CAO, the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights, and the division of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MTPI) are based. Until two years ago, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which tried those responsible for the 1994 genocide, was based in Arusha.

Arusha is bucolic enough to avoid distractions, but it has the infrastructure to host high-level summits – it is the Sharm el-Sheikh of East Africa.

Why Tanzania? “Tanzania often appears as a relatively neutral country and a rather positive force in the region,” explained Yolande Bouka of the Institute for Security Studies. The imposing figure of Julius Nyerere, the first president of the country, enjoys the same qualifiers.

The guiding principle of his rule – that of independence and African socialism – was enshrined in the Arusha Declaration and spawned a long relationship with Scandinavian social democrats.

But he is most, and rightly, celebrated for the role he played in African liberation – particularly in southern Africa. It was also his collaboration with Nelson Mandela that brought an end to Burundi's 12-year civil war, with Mr. Mandela's unilateral decision to deploy South African troops to protect political leaders returning from exile. .

Who supported the agreement for peace in Burundi? The agreement aimed to end the conflict and the cycle of massacres, including genocide, which had bloodied Burundi since its independence in 1962. Trust was a central element of the agreement. In short, the Tutsi minority had to give up its monopoly over the army, where it occupied a dominant position, in order to guarantee its physical survival; the Hutu majority had to establish a democratic process to obtain representation without resorting to arms.

According to Paul Nantulya of the African Center for Strategic Studies, a Pentagon-based agency, the meditation “was about finding a balance between two extremely complex issues. The first question was how one could ensure full political participation of the Tutsi minority even though their prospects of winning competitive elections would remain slim in the near future. The second question was how to dispel the deep distrust of the Hutu majority towards the armed forces”.

The resolution of these dilemmas required a power-sharing agreement based on the over-representation of minorities and the creation of a coalition; the implementation of protocols guaranteeing the equitable participation of all parties within the three branches of government and all national institutions, including state-owned enterprises; constitutional provisions to discourage the concentration of power in the hands of a single party or group of parties; and the creation of a unified army.

In the political crisis in Burundi, the opposition mainly blames President Pierre Nkurunziza's party, the CNDD-FDD, for extending its control over political and military institutions - in violation of the Arusha Accords. The CNDD-FDD, reluctant to lay down their arms, did not sign the Arusha Accords. Accordingly, he asserts that he is not bound by the agreements, which he considers outdated. He argues that the Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement, which he signed in 2003, nullifies and replaces the Arusha Accords.

Ms Bouka of the ISS considers this position to be a fraud, as the Comprehensive Ceasefire Agreement stems from the Arusha Accords and cannot be considered independent of its provisions.

“Arusha remains a strong but increasingly controversial symbol of the prospects for regional diplomacy,” an African diplomat based in Addis Ababa told IRIN. His concern is whether the region now has the leverage to bring Mr. Nkurunziza to the negotiating table and prevent the escalation of violence in Burundi. "We risk being perceived as unstable, without the strength to see things through."

The Case of RwandaThe United Nations-sponsored Arusha Accords were signed by the Rwandan government and rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) before the 1994 Rwandan genocide. he majority Tutsi exiles left for Uganda and returned to the country in 1990 to wage war against the largely Hutu-dominated government – to put it simply, a situation the opposite of the situation in Burundi.

The agreements provided for the sharing of power to include representatives of the civil opposition to the regime of President Juvénal Habyarimana. The many divisions within the political parties and Mr. Habyarimana's contempt for “pieces of paper” complicated the negotiations in Arusha.

The Accords, finally signed in 1993, were never implemented. In April 1994, the plane bringing Mr. Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira from Dar es Salaam was shot down in Kigali – no one really knows by whom – triggering a genocide targeting Tutsis and liberal Hutus. The subsequent military victory of the RPF put an end to the apparent political need for an agreement.

A better peace? By their nature, peace agreements usually result in a sharing of power between armed men; they therefore generally do not take into account issues of transitional justice and accountability. The usual steps are the establishment of a ceasefire and the organization of elections supervised by the United Nations; then the attention of the international community shifts elsewhere. Few are the explicit attempts to engage the communities that have suffered the most from the conflict or the mechanisms to ensure respect for peace in a sovereign country.

“We know that we reward those responsible for the deaths and violence, but what can we do without them? “, noted Ms. Bouka.

A peace negotiated by the elites and resulting from an agreement reached with men accustomed to acting with total impunity can prove fragile. “In some cases, we see the warning signs [of problems to come], but we are so concerned about the current stability that we are letting things slip,” Bouka said.

She added that there were many examples of the closing of political space in Burundi and the growing intolerance of the CNDD-FDD towards regional diplomats who did not intervene soon enough.

oa/ag-mg/amz

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev