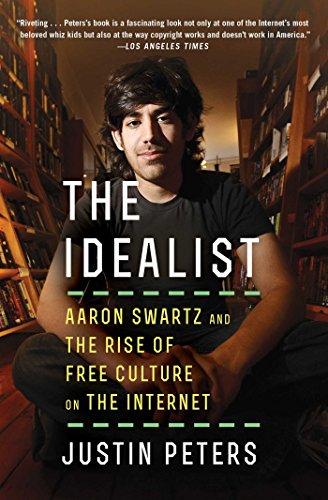

Aaron Swartz, the mysteries of an idealist<

Reading time: 71 min

On January 4, 2013, Aaron Swartz woke up in excellent mood."He turned to me," recalls his girlfriend Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, "and said a goal in white:" This year will be great "."

Swartz had reasons to be optimistic.For the past year and a half, he was indicted for computer fraud, an apparently endless test which had exhausted his financial and emotional resources.But he had new lawyers, who worked hard to find common ground with the government.Perhaps they were going to conclude an acceptable agreement.Perhaps they would go to court and win.

"We're going to win, and I'm going to start working on all the things that interest me," Swartz told his girlfriend that day.Not that he was idle.In addition to his work for the International Computing Consulting Company Thoughtworks, he had become a editor for The Baffler magazine, had done a substantial research on the way of reforming drugs on drugs and had overcome almost 80% of a huge summary of the intrigue of the Infinite Jest novel.

But Swartz put the bar very high and there was always more to do: new books to read, other programs to write, new ways of contributing to the countless projects in which he was committed.

Cheese cheese cheese cheese

Swartz and Stinebrickner-Kauffman started 2013 with ski holidays in Vermont.The daughter of the ex-girlfriend of Swartz, the journalist specializing in new technologies Quinn Norton, joined them.Swartz loved this little more than anyone in the world.

He loved children, and on occasion behaved in a kid himself.Difficult to pathology, it only ate bland food: cheerios without anything, white rice, pizzas with Hut pizza cheese.He told his friends to be a "supergutor", extraordinarily sensitive to tastes - as if his taste buds constantly suffered the shock of going from an obscure room to a lively light.

Although he described himself as a "specialist in applied sociology", Swartz was best known as a computer programmer.His current project, software he had baptized Victory Kit, was on the right track.Victory Kit was to be a free open-source version of the expensive community organization software used by groups like Moveon-the kind of software usable by activists from around the world.

Some of these activists had come to listen to Swartz present Victory Kit at a conference in northern New York State on January 9.But at the last minute, he had decided not to speak.

His friend Ben Wikler says that his intervention depended on another person's commitment to agree with him so that their code is in open source.Having failed to obtain this commitment in time, Swartz had decided to give up his intervention."I remember that his immobility annoyed me," said Wikler.

The possibility of a wedding

Swartz had principles he kept a lot."Aaron generally thought that being picky on these kinds of things made the world better, because it really pushed people to make the right choices," reports Wikler.

He never signed any contract likely to encourage the Patent Trolling.He had very stopped ideas in terms of clothes and wore t-shirts whenever he could."The costumes," he wrote on his blog, "are the physical proof of the hierarchical distance, the validation of a particular form of inequality".

He was not dogmatic on all subjects.Opposed to the wedding forever, he was starting to tell himself that he was wrong.On Friday January 11, Stinebrickner-Kauffman made a stop at Wikler.She and Swartz had to come and dine later in the evening, but she had gone by her own before.

While playing with Wikler's newborn baby, she said that Swartz told her that after the end of the case, he might consider marriage.If it was possible, then nothing was impossible.

But less than three kilometers away, in a small dark studio, Aaron Swartz was already dead.

At the beginning of each year, Aaron Swartz put online a list of everything he had read in the previous twelve months.His list for 2011 included 70 pounds, of which twelve were for him "so great that my heart jumps from joy at the idea of telling you about it even now".

One of them was the trial of Franz Kafka, the story of a man trapped in the gear of a vast bureaucracy, confronted with accusations and a system defying any logical explanation."I read it and I found it extremely exact - the details perfectly reflected my own experience," said Swartz."It's not fiction, it's a documentary."

When he died, Swartz was 26 years old and has been the subject of prosecution of the Department of Justice for two years.In July 2011, he was accused of accessing the MIT computer network without authorization and having used it to download 4.8 million documents from the JSTOR online database.For the government, his acts under the American Criminal Code and made him incur a maximum sentence of 50 years in prison and a fine of $.

Unanswered questions

This affair had undermined the finances of Swartz, his time and his mental energy and generated in him a feeling of extreme isolation.Even if his lawyers worked hard to reach an agreement, the government's position was clear: whatever the agreement agreed between the two parties, he would have to include at least a few months in prison.

An prolonged indictment, an intransigent complainant, a corpse - here is the facts.Who are overwhelmed by the questions raised by the family, friends and supporters of Swartz since his suicide.Why did the MIT absolutely wanted to file a complaint?Why was the Department of Justice so strict?Why did Swartz hanged himself with a belt, choosing to end his life rather than continuing to fight?

Backlog / quinn Norton via Flickr CC License by

By killing ourselves, we abandon the right to control his own story.In gatherings, on forums and in the media, you will hear that Swartz was shot down by depression or that he was trapped by a political battle, or that he was the victim of a statevindictive.

A ceremony in his memory, held in Washington in early February, turned into a battle around his inheritance, where the bereaved cried on their disagreement on the changes in politicians to be undertaken to honor his memory.

Let it develop, and destroy it

The Aaron Swartz case is a hell of a puzzle.He was a programmer resistant to any description, a millionaire.com who lived in a rental studio.He could be both an annoying employee and an effective expert to identify problems.He had the gift of making powerful friends and making them flee.He had dozens of interests and devoted himself to each of them.

In August 2007, he wrote on his blog that he had "committed to developing a complete catalog of all books, writing three books (project widely abandoned in the meantime), [informing himself on a project with non-purposeLucrative, help the realization of an encyclopedia of trades, create a new Weblog, found a startup, serve as mentor with two ambitious Google Summer of Code (stay connected), build a Gmail clone, create a new reader online, start a journalist career, make an appearance in a documentary and do research and co -write an article ”.And his productivity found himself hampered because he had fallen in love, which "takes a monstrous time!".

It was fascinated by major systems and the way in which the culture and values of an organization could generate innovation or corruption, collaboration or paranoia.Why does a group of teachers and professionals agree to treat a 14-year-old kid like his equal while another spends two years to be tested in a completely disproportionate trial compared to the so-called crime committed?How can a type of organization develop a young man like Aaron Swartz, and another destroy it?

The need to repair

Swartz believed in the virtues of collaboration to help organizations and governments to work better, and his first online experiences had shown him that it was possible.But he had more talent to start things than to finish them.He saw obstacles as well as opportunities, and these obstacles often came to the end of his strength.

Today, in death, his refusal of the compromise takes on a new face.He was an idealist, and his many projects - attended and unfinished - are a testimony to the barriers he had put down and those he was trying to postpone.It was the heritage of Aaron Swartz: when he thought something was broken, he was trying to repair.If he failed, he tried to repair something else.

Eight or nine months before his death, Swartz fixed on Infinite Jest, the enormous and complex novel by David Foster Wallace.He thought he could disentangle the sons of the plot and assemble them into a coherent and easily decomposable whole.

It was a difficult problem, but he thought he could solve it.As his friend Seth Schoen wrote him after his death, Swartz thought it was possible "to arrange the world mainly by carefully explaining it to people".

It’s not that Swartz was smarter than average, said Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman-he just asked better questions.Project after project, he was investigating and tinkered to extract the answers he was looking for.But in the end, he ended up with an insoluble problem, a system that didn't make sense.

Aaron Swartz was born in November 1986. The eldest of three brothers, he grew up in Highland Park, Illinois, a wealthy suburb north of Chicago, in a large and old house of false tudor in a wooded property, not far awayField welcoming the summer music festival Ravinia.

Robert, his father, was a computer consultant, and his mother, a housewife, loved knitting and pearl work.His grandfather, William Swartz, presided over a signs company and joined Pugwash, an organization advocating the disarmament which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995.

"The idea of trying to do good and making the world better permeated our way of considering things," said Robert Swartz."The idea of not being interested in objects, money, acquisitions was our way of seeing the world."

Aaron was an early child, who was able to read very early.At 3 years old, he remembers his father, he read a paper on the refrigerator and asked his amazed mother: "What is this free party for families in the city center of Highland Park?"

When he aged school, he joined the North Shore Country Day School (NSCDS), a picturesque private school in Winnetka, Illinois.The school was 9 km from his home, so it was not easy for his friends to come and play at home.Aaron found ways to have fun alone - playing the piano, reading, having fun with his brothers.

Fascinated by the puzzles

Very young, he was an expert in the handling of machines and fascinated by the puzzles."Small, he was interested in magic squares - squares of 3 by 3, where in all directions the added figures give the same result," recalls Robert Swartz:

The Swartz family was one of the first in the area to have internet access, before the advent of graphic browsers.Aaron had computers very early and he was carrying out a huge class laptop in class.

He was building websites for himself (aaronsw.com), for his family (swartzfam.com), for people interested in "the russian mountains of the case against Microsoft" (Redmond Justice), for those who wanted to convertText in ASCII Binary code and again in text (Binary Translator) and for the Fan Club of Star Wars Chicago Force.

"He came to a Jedi council (name we gave to our board of directors) one day, his parents had deposited him," recalls Phillip Salomon, a member of the group.His first pseudo Aim was "Jedi of Pi".

It was around this time that Aaron began to be bored at school."He came to see me to ask me for things to read," says Robert Ryshke, director of the NSCDS high school from 2000 to 2005:

Swartz was convinced that North Shore Country Day did not meet his needs (nor to those of any other student).In the summer of 2000, just before he started high school, he launched a blog called Schoolyard Subversion."Seriously, who really cares about the length of the Nile, where who discovered the cheese?", Could we read:

Despite its small size, its supernatural intelligence and its iconoclastic side, Swartz was not socially isolated.He had friends, participated in scientific Olympiads and sports teams.

Class videos shot towards this time reveal a young person in the sense of moron humor (one of them, a six-minute scene showing a puppet-chaussette that announces the weather, earned him a F, note-t-It, because it lacked "exact data" on the weather) and maintaining good relations with his comrades -or, in any case, with those who played by her side in a crazy "Telenovela" of 11 minutes whoFinish on a swartz wearing a sombrero, shot down by a boy in purple football jersey ("Ay, yi, mi muerto! Mato! Mato!", He screams, with a passion inversely proportional to his grammar level).

The dissatisfaction of Swartz had less relation to its peers than with the broader concept of organized education.At the start, he was determined to reform things from the inside and his blog was overflowing with optimism on nomadic schools and stimulating teachers and a "big meeting" during which Swartz submitted to Ryshke, the director of the main classes,Books on education reform.

A life marked by impatience

His reforming ardor eventually calmed down, and Swartz focused on developing an outing strategy.It was the beginning of a whole life marked by impatience in the face of unpleasant situations.Instead of trying to adapt to what he considered as rigid and broken institution, Swartz was trying to make them adapt to him.And when they didn't change, he left.

"We mentioned the possibility of going to college earlier, to opt for the path of little genius, but I believe that taking English and algebra lessons did not interest him," explains Ryshke:

Swartz told on his blog how he had finished his first year of high school by expressing his complaints at a school meeting:

Neither Robert Ryshke, nor any other NSCDS source recalls ("it would look like Aaron enough to do that," admits Ryshke).Anyway, this story reflects its conviction that high school was a malicious enemy that had to be overcome.

"The Internet was based on free access"

No matter what others thought or said, Swartz knew that his decision was the right one ("he claimed to have tried to convince many of his comrades to abandon school with him, and have had no success," said TarenStinebrickner-Kauffman, reporting the memories of Swartz of that time. "I can only imagine what their parents could think.").In the summer of 2001, at 14, Swartz left North Shore Country Day.

While he was fighting to make his way in real life, Swartz's online life prospered.He accompanied his father on a business trip, where he attended a conference given by Philip Greenspun, professor and defender of open source software.

Greenspun had a company, Arsdigita, which sponsored a competition where adolescents competed to build useful and non-commercial sites.Swartz entered the competition in 2000 and was among the finalists for its contribution, The Info Network, an encyclopedia in which everyone could participate (it was months before the launch of Wikipedia, in 2001).

"Providing people on the World Wide Web is" real information "is the 13 -year -old Aaron Swartz job.It is tired of all the banners of advertising, sponsorship and all the diverse and varied “junk” that pollute the screens, "explained the Chicago Tribune in a June 2000 article on Swartz's participation in the competition.

"The Internet was not made for that.It was based on free access and freedom, not on advertising, ”said Swartz in the gallery.It didn't matter that Swartz's friends and family were the only ones to use The Info Network, or that, know why, the best assessed entries concerned reserve players from Chicago Cubs, like Shane Andrews and Jeff Reed.

Very young, he had discovered his passion: finding information, organizing it and sharing it with all the people likely to be interested.

A network of friends created via the Internet

The web also enabled Swartz to have a fulfilled social life."I developed my most important online relationships," he wrote at 14 in April 2001:

He connected to his online network via his blog, launched in early 2002 and which was not long in becoming popular among the fans of new technologies.Same teenager, Swartz had an alert and clear, prolific pen with well -stopped opinions.

If he often seemed aggressive or disdainful, it was probably because he was trying to compensate for his young age - which he was very aware very early and of which he did not speak.Wes Felter, researcher and blogger who knew him at the time, says that Swartz rejected the "insignificant arguments" that he was only a kid and did not have enough experience to display his opinions:

"I find that what you do is pretty cool"

Many of the SWARTZ correspondents were involved in the movement of the semantic web, an initiative aimed at structuring the world online so that computers decompose it more easily.The .com boom had quickly caused immense growth and the web then looked like a city without land use plan.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an organization created by the inventor of the World Wide Web Tim Berners-Lee in 1994, milita for a standardization of the Internet-to guarantee that the pages would appear correctly and that transmission and recoveryInformation would gain in quality, not the opposite.

The W3C worked a lot through mailingist.In these email chains, participants solved code problems, debated the issue of standards and threw the foundations for the Internet's future.

Although the lists were mainly used by researchers and professional programmers, everyone could participate."There was a tradition of meritocracy born from the start of the Internet," said Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive."This means that if you have talent and you provide your help, you become a first -class member of any group you want to belong."

Aaron Swartz, 13 at the time, postped his first message on the Rdfweb-Dev group on August 21, 2000:

A kid obsessed with rails, not by trains

Many kids are obsessed with trains.Much less are by rails, switches and signals.But already at the time, Swartz was fascinated by the original shortcomings which prevented major systems from working as much as possible.

It was precisely the kind of thing that concerned W3C researchers.Swartz suited them perfectly.

Around the same time, he also joined a working group dedicated to the RSS.This news reading technology had been developed by Netscape originally, but the company having lost all interest in its maintenance, online hackers had resumed the torch.

In 2000, two groups of programmers wanted to take the RSS to two different directions.One of them was a group affiliated to the semantic web, which proposed to rewrite the standard in order to include metadata easier to decompose.Swartz joined their ranks and contributed to the development of a standard called RSS 1.0.

Many ONCROLOGIES said SWARTZ had created or co-created the RSS.This is not true: it belonged to a dissident group which had created a version of the RSS used by relatively few people.

This did not prevent his contributions from being very real and valued, and his collaborators were always surprised when they discovered that Swartz was a teenager.

"At the start, you meet these people in writing," recalls Dan Connolly, creator of affiliated software 15 years at W3C.“The written type of codes, makes intelligent comments;As far as you are concerned, it's your equal.And then you discover that he is only 14 years old, and you fall from the clouds. "

In December 2001, Aaron Swartz told an unusual dream on his blog:

Whether he knew it or not, this dream world he described really existed, the water slides less, and Swartz was going to become one of his most important heirs.

A dream come true

There is a photo of Aaron Swartz adolescent sitting on a bench, dressed in a "Gnu’s Not Unix" t-shirt, speaking with law teacher Lawrence Lessig.It's a bit of a family photo, the photo of two generations of cyber-idealists.

Aaron Swartz and Lawrence Lessig / Rich Gibson via Wikimedia Commons.Click on the image to enlarge

The Swartz t-shirt comes from a group called Free Software Foundation and the slogan refers to the operating system created by the Foundation.GNU/Linux (GNU for "GNU’s not unix") is a free alternative of community origin to the UNIX operating system, designed in the 1980s by a software developer named Richard Stallman.

In the 1970s, Stallman was one of the many programmers affiliated with the artificial intelligence Lab du MIT.As Steven Levy says in Hackers, his story of the origins of modern IT, AI Lab was a kind of programming utopia that attracted computer enthusiasts of all horizons - a Brook Farm of theDigital era.

It was a horizontal and non-hierarchical system, where you were judged on the scope of your work, not on your age, your status, your title or your diplomas.

"There were people who only passed, who were neither students nor staff members.They were just there, and they helped us, "said Brewster Kahle, a member of AI Lab in the early 1980s." And this opening was wonderful and very creative. "

Inspired by "the last of the real hackers"

Stallman and his co-hackers wrote and maintained the essential software for laboratory research.But in many aspects, it was less a workplace than a place of political awakening.

"The hackers openly spoke of changing the world thanks to software, and Stallman acquired the instinctive disdain of the hacker towards any obstacle preventing to reach this noble cause," writes Sam Williams in Free As in Freedom, his Biography of Stallman in 2002:

Steven Levy describes Stallman as "last of the real hackers" - all the affiliates to AI Lab, he was the one who had organized his life around the group's ethics most feverishly.If the others went to the private sector and sometimes made a fortune, Stallman has never lost its radical idealism (from this angle, it is a bit of Ian Mackaye of IT).

Stallman, who has kept an office in what MIT now describes the Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, founded Free Software Foundation in the mid -80s, which he still presides today.This organization is devoted to the idea that free software ("free [free] as in freedom, not free [free] as in beer") are a moral imperative.

Swartz did not personally know Stallman, but the programmer's principles inspired him, as well as the fact that he has overseen an organism that took ethics seriously while being effective.

In 2002, he attended an intervention by Stallman during the O’Reilly Open Source Convention."The most interesting thing I learned ... It is Stallman's very human side," he wrote later:

"A 14 -year -old teenager for the project"

At the same conference in 2002, it was Lawrence Lessig - Le Richard Stallman of the copyright movement - who made the main speech.

Lessig, in Stanford at the time and today in Harvard, wrote a lot about the injustices of the American law on copyright.Companies put pressure on the congress so that it continues to extend the scope and duration of copyright protections, he believes, which maintains documents outside the public domain and stifles innovation created thankssharing and remixing.In the introduction of his 2004 free culture work, Lessig notes that "all the theoretical glimpses developed here were by Stallman decades ago".

In 2001, Lessig invented his own variation in the Free Software Foundation of Stallman, an organization he called Creative Commons.He wanted to reform the laws on copyright by giving creators of content more possibilities to disseminate their work - allowing them to specify, for example, that a photo was usable free of rights or that one could adapt it without havingto request authorization.

Lessig hired Lisa Rein, a programmer and archivist, to help him build the Creative Commons website.She in turn suggested that Swartz, which she had met in the semantic web community, could supervise the establishment of site metadata.

"I'm not going to lie to you and tell you that it was not difficult at the time to convince these people that I needed a 14-year-old teenager for the project," she recalls."Politically, it cost me dear at the time.Until they meet it.No one did not understand anything, until they meet it. "

Ben Adida, one of the project participants, remembers Swartz as an active and important element, "an extremely talented software creator who is 14 years old and wear a T-shirt three times too big for him".

They both worked closely on the implementation of metadata, and not always in perfect harmony."He put the bar incredibly high, and we were not up to the task," recalls Adida."He was very critical of my work, and said it publicly.He was quite hard with me ”.

"Either a superhero, or a super-hoping"

Swartz was very demanding with those around him, but he also kept him very keen to establish links with his new colleagues.

In April 2002, he took the plane for San Francisco to attend a Creative Commons and Lisa Rein event accompanied him to visit the city.She considered that she had the duty to make her meet the right people."In a way, I decided that he would become either a superhero or a super-hoping," she explains.

REIN brought her to meet all the people she knew in the world of open-access, who were going to become her friends and collaborators.The experience opened the eyes of Swartz and made him understand that he was not alone.

"I know that Aaron spent much of the beginning of his life fighting with the fact that his interest and curiosity were awake by a lot of things that did not interest others," explains Seth Schoen, technologist atThe Electronic Frontier Foundation.The latter met Swartz in 2002, when he was 23 years old and his future friend had 14:

City Museum of St Louis / Quinn Norton via Flickr CC License by

"Less mature than the others, but not much"

Swartz had found his own, in flesh, not only in the form of names on the line of the recipients of a broadcast list.From 2002 to 2004, he spent a lot of time in their company, spectator and intervening numerous conferences on emerging technologies and technological problems (at home, he argued a lot with his brothers and parents to find out who had the right to'Use family segway).

Despite his youth, Swartz was not treated as an adorable mascot in the world of technology."Okay, socially, there were a lot of nerds," recalls Wes Felter:

The days were going to listen to conferences, and the post-dinner activities could include "an expedition to the Apple Store to go see the brand new at the time, the one that looked like a tablet attached to a globe", As Joey" accordion Guy "says in recent memories published online.

Stanford, a new place to repair

In 2004, Swartz had contributed to the launch of Creative Commons, worked on the RSS 1.0 standard, created and maintained a popular blog and got the hands of other projects, young and old.

But he was also about to be 18 years old, and despite his distrust of organized education, we expected him - parents and almost all the rest of the world - that he goes to theuniversity.In the summer of 2004, he enrolled in the Stanford University.

For Swartz, Stanford moved him away from the dream world of Creative Commons and made him come back to everything he had hated in high school.A week after his arrival in Palo Alto, he blogged that "the exceptional intelligence of most of Stanford students (and teachers) did not particularly hit him."

The university was not an ideal intellectual world - it was just a new place to repair."If I wanted to launch a more effective university, it would be quite simple," he wrote during his third day in Stanford:

Swartz lived in Roble Hall, in an apartment with three other people."He was a pretty introverted guy, I was a pretty introverted guy," recalls his roommate, Rondy Lazaro.“Some people from his building were aware of his programming work.For them he was the Aaron Swartz. ”

For most people, however, it was only the guy at the end of the corridor with the lying bike and the closet furniture.

Swartz studied sociology."The other evening, when [erased name] asked me why I went from computer to sociology, I replied that computers was complicated and that I was really not good,Which is not true at all in reality, ”he wrote on his blog."The real reason is that I want to save the world."

Asleep in Midpage / Quinn Norton via Flickr CC License by

In several posts, he tells of his experience in Stanford as an anthropologist takes notes in the field.He wrote about group thought in campus and criticized his courses.From time to time, his loneliness pierced the shell:

SWARTZ was perhaps not the most objective narrator of his experience at university.Many of those who knew him in Stanford say that it was not an absolute lonely and that he was always ready to participate in the conversation.

Difficulties in establishing social ties

But his blog - that he had chosen not to share with other students - is not the work of someone who has fun in his first years of college.His lessons were not interesting enough or motivating enough and he languished for the one he nicknamed TGIQ ("The Girl in Question", "The girl in question"), "who always managed to" disappear before [he]cannot catch up with it ”.

Instead of chatting with his first -year comrades, he haunted teachers like Lessig."It's great, except that it bored me to bother them," he wrote.

The worst of everything was that his comrades did not think like him.Before meeting the Creative Commons team, he had trouble finding people with whom he could tie a link."I remember that he really hoped that it would change by leaving for Stanford," says Seth Schoen:

Their curiosity was probably not manifested in the same way as his - they took Stanford as she was and drawn the best possible party, rather than questioning all that the university represented.

However, he tried to make things work.In 2005, he participated in the launch of the Roosevelt Institute Campus Initiative, a group encouraging students to engage in politics.

But he gradually disengaged from school, spending more and more time out of the campus with people involved in political activism and data freedom.In addition, he completed his studies by reading a lot."He read more fictions when he was an 18 -year -old computer genius that I read today as part of my higher education in literary creation," recalls Kat Lewin, one of his roommates.

Two books change his vision of the world

Summer before he arrived in Stanford, Swartz read two books that changed his vision of the world.

Moral Mazes, which he would later describe as an absolute favorite book, is an ethnographic study of the managerial culture of the American company.Robert Jackall looks at the institutional logic of the business world and explains how the dilution of responsibilities and organizational narrowness create a culture that rewards managers when they make the wrong choices.

In Understanding power, which develops the same kind of point of view, the linguist and political activist Noam Chomsky explains how the structures of power push people well to do horrible things.

These two books are indictments of the bureaucracy - the way in which giant organizations harm foreign bodies coming into contact with them and its members who refuse to play the game. For someone like Swartz, predisposed to resistThe idea of being a gear in a machine was the intellectual justification he needed to tackle the industrial education system.Like the North Shore Country Day School before her, Stanford never had the slightest chance.

End of the Episode Fac

Swartz jumped on the first opportunity had to fold luggage.She took the form of the essayist and entrepreneur Paul Graham, founder of the company Y combinator in 2005. Graham, who became rich in millions by selling his business viaweb in Yahoo!, Thought that talents as brilliant and insatiable asSwartz had to leave school and start building things.

He invited emerging entrepreneurs to send him start-up proposals in the field of new technologies;He chose those who liked him and took their creators to Cambridge, Massachussetts, to put them on track the space of a summer.

Swartz offered Graham a thing called Infogami, a platform designed to help its users build structured websites, rich in content and with data -run architecture.It was a logical conceptual progression after the semantic web projects in which he had bathed and she became one of the eight companies to be funded that year.

Shortly after the departure of Harvard de Mark Zuckerberg, direction the Palo Alto start-up culture, Swartz made the opposite path, abandoning California after only one year to set up a start-up on the East Coast.End of the EPLE episode.

Infogami made a flop - there is no other way to say it.Swartz did not have the experience necessary to build such a ambitious project from nothing.He had trouble attracting investors and verbalizing the specific problem that Infogami was supposed to solve.

In addition, Swartz and his roommate/collaborator, a young Danish programmer called Simon Carstensen, did not form a great couple of partners.When Carstensen arrived in the stifling little room of the MIT they were going to share for the summer, it was the first time that the two men met."I remember sitting in this dormitory, coding, and having been very hot," said Carstensen.

Swartz rewritten a large part of the Carstensen code, and at the end of the summer, the Danish returned to Europe and did not rework on Infogami.Swartz stayed in Boston, but his start-up began to make him lose patience.

Infogami to Reddit

He was alone, lived with Paul Graham, and had morale at zero:

Above the same time, two other participants in Compainator needed help with their own start-ups, a community site called Reddit.Graham's solution was simple: Infogami was to merge with Reddit, creating a new mother-by-laws called Not a Bug.Swartz moved to Davis Square in Alexis Ohanian's apartment and Steve Huffman and set out to work.

Dr Miyagi When Asked If He Could Break Through A Stack of Bricks Responded Asking Why He Should Know How To Do that… https://t.co/07n0xj79kl

— Ekerombeta n'ekerongo Wed Sep 16 03:41:22 +0000 2020

The story of Swartz's passage to Reddit is complicated.It was not involved in the conceptualization of Reddit;The project was already on foot when it went on board.If Ohanian and Huffman did not consider him as a co -founder, Swartz still often used the word.

What we can say is that Swartz was unhappy at Reddit, and that the Reddit team was not happy with him either.

The starting project was that Huffman helps Swartz for Infogami while Swartz would help him for Reddit, and the two projects would start from a joint program that they would build in two.

Huffman was very enthusiastic about working with Swartz, whom he considered a talented programmer."There was a moment, the first two months, where we said to ourselves: OK, we're going to start this new thing and it's going to be bigger than Reddit, bigger than Infogami," said Huffman."And it became quite clear after a few months that it was not going to happen like that."

The launch of Infogami was not going well and Swartz was demoralized."He was tired of working on Reddit, and I never wanted to work on Infogami," reports Huffman."It was the start of the end."

Personal development quest

For months, Swartz did not work on Reddit, but continued to live with Huffman and Ohanian.His changing mind focused on other things, including a failed application for a position on the board of directors of the Wikimedia Foundation.

And, as at the time of his blues in high school or college, he unloaded his frustrations on his blog."I don't want to be a programmer," he wrote in May 2006, at 19:

Swartz's personal development quest would cause an unpleasant working environment.

Huffman being the only full -time engineer in Reddit, the success of the site was not guaranteed.However, in October 2006, sixteen months after the Reddit Foundation, Condé Nast bought the Company for an undisclosed sum, somewhere between 10 and 20 million dollars.

Part of this money returned to Graham and another to Chris Slowe, part -time programmer who had shares in the company.Swartz, Huffman and Ohanian shared the rest (Swartz gave part of his part to Simon Carstensen, to reward him with his work on Infogami.)

The agreement stipulated that the Reddit team would move from Boston to San Francisco;It was not planned that Swartz, openly unhappy of his situation, accompanies them.But for any reason - masyochism, sense of duty, or conviction that a change of landscape could improve things -, he decided to go back to the west.

The Reddit team worked in Wired's office, in a free corner specially for them.This physical environment looked a lot like the idealized “modern design loft” of which a teenage swatz had dreamed in 2001-a large open space with a personal chef who made breakfast for everyone.

But as one could foresee, Swartz was unhappy, absolutely unsuitable for business life.Each meeting, each banality had to represent a moral labyrinth for him.He stopped coming to the office, wrote blog posts criticizing his colleagues, left for impromptu trips to Europe and worked very little.

Once again, he was trying to detach himself from an environment that had not lived up to his expectations.But this time, he could not leave by dictating his own conditions.Less than three months after the materialization of the sale in Condé Nast, Ohanian and Huffman asked him to leave.

A blog post on suicide

Above at the time when he was sent back from Reddit, Swartz wrote a long story on his blog on a man who hungry before committing suicide:

"Alex" was initially called "Aaron" (Swartz removed the post for a while, then changed the name of the character when he put him online).

Alexis Ohanian, whose girlfriend of the time had tried to commit suicide less than a year earlier, called the police and made sure that she was going to check that Swartz was fine, which was the case.Later, he explained that this blog post was a misunderstanding of fiction:

Impossible to say if this post was a melodramatic story, a call for help or a morbid premonition.At the time in any case, he served as a dramatic and final end for an unsatisfactory chapter in his life.Swartz was 20 years old and found himself without work.But at least he felt that he had control of his life again.

Reddit, "just a list of links"

Sooner or later, any true believer has the opportunity to deny his principles - to put money or comfort before what he claims to be the most important in his eyes.At the end of the 1970s, the AI Lab of MIT disintegrated.

Several programmers had left to train their own company, symbolics, which built and sold Lisp machines and the software to make them work.It was the same computer language as, until that time, AI Lab hackers developed for free.

Stallman lived him as a gigantic betrayal and took refuge in the last bastion of idealism of an environment where he once flourished.

The last of the real hackers performs real programming prowess to match all alone - each Symbolics software update, while ensuring that the free version would be as good as the paid.Shortly after, Stallman left AI Lab to launch the Free Software Foundation and make his idealism the work of a lifetime.

The separation of Swartz and Reddit, if it was not as long and openly antagonistic as the Stallman/Symbolics battle, was just as ideological.Although he did not verbalize it at the time, he was clear with hindsight that Swartz hated the feeling of doing something for money.After the sale at Condé Nast, he described his feeling of guilt of having received so much money for a project that in his eyes was so insignificant:

At the crossroads of data and authority

Leaving Reddit Pousa Swartz to re -examine your life.Any unique project could be an overwhelming task, a chore or a chiantissime project.The solution to this problem was to engage in "all the interesting projects that arose".

He worked on another start-up, Jottit, with his former infogami partner Simon Carstensen.He also led to the launch of the Brewster Kahle open library, the Internet Archive, ambitious effort to create a description page of each existing book.

The projects that interested him were increasingly at the crossroads of data and authority.Swartz had grown up in a family where activism was erected by virtue and his first work with Creative Commons had given him a cause well.

In October 2002, at 15, he went to the Supreme Court, invited by Lawrence Lessig.The law professor defended the complainant in Elddred v.Ashcroft, a crucial case in the field of modern copyrights.Lessig argued that the court should cancel the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, which extended copyright protection significantly.He lost, but the experience was a trainer for Swartz - which was an ardent reformer of copyright laws all the rest of his life.

In the years that followed, both Lessig and Swartz became more and more openly political.In 2008, the law professor participated in the foundation of an organization called Change Congress, which encouraged citizens to do what his name indicated.

Swartz got there with ardor and joined the group's board of directors.This project sparked an interest in electoral policy at home.Swartz contacted friends in Washington, probing them about the functioning of the system and asking them to improve it.

"When you talk to the people of Silicon Valley, they often tell you that politicians are stupid," said Matt Stoller, one of the people contacted by Swartz:

A programmer with political value

Swartz was quick to realize that his talent for accessing information and synthesizing it could have a political value - that he was better programmer and data collector than most other activists and that his activism was more ardent than that of mostSoftware aces.

Swartz helped found a group, the progressive changed Campaign Committee, devoted to the election of progressive candidates in the congress.He obtained a Sunlight Network scholarship to launch a site called Watchdog.net, which gathered information on electoral documents and campaign funding and gave its users tools to manipulate and present this data themselves.

But Swartz was not long in laying his eyes on a bigger fish: Pacer, the electronic warehouse of federal judicial files.Pace content is public and anyone can access it via the web for a small sum (10 cents the page today).

For Carl Malamud, a activist advocating transparency, these documents should not have cost a single penny, because they were government products and therefore not subject to copyright.

Dinner at Willow Cottage (Some Piracy) / Quinn Norton via Flickr CC License by

In 2008, Malamud appealed to those who thought like him to collect a maximum of documents in Pace during a trial period during which the documents would be downloadable for free in certain libraries.

This call for action naturally found an echo in Swartz, a declared enemy of restrictions on copyright and supporter of open data.In September 2008, he went to a library in Chicago and installed a PERL script which extracted a pacer document every three seconds.

Before the library realizes it and stopped it, he had time to download 19,856,160 pages, which he gave the site advocating the transparency of Malamud, public.resource.org.

For Swartz, the decision to install this Perl script represented a subtle but spectacular change in ideology and method.He had always been convinced that the information wanted to be free.And he had just played the role of liberator.He had also chosen to make fun of the federal government, seriously fingering a reluctant system for change.

Although he had nothing illegal, this feat drew FBI's attention to Swartz and Malamud.Swartz later obtained his file at the FBI, which indicated that agents had watched the family home at Highland Park.

This FBI dossier, he said, was "truly delicious".At the time, all of this seemed funny - federal agents could also be upset by such a derisory fact.

But Malamud now thinks that Pace's downloads played a role in the government's subsequent determination during prosecution in the JSTOR affair.In their eyes, Swartz was a repeat offender, a Robin of the woods of the data.It was not nothing.

In 2008, Swartz began to get tired of San Francisco.He had been there for 18 months and found more and more that the city was superficial."When I go to the cafe or to the restaurant I cannot avoid people who talk about loading of load or databases," he wrote:

At the end of spring, Swartz left the city for good and returned to Cambridge, which he described as "the only place where I never felt at home."

He spent most of his time working in a building shared by Harvard Square called the Democracy Center, which housed several progressive activists.His office, upstairs, wore a broken balcony and a hole in the wall, which meant that he could hear everything that was going on.

His neighbor was Ben Wikler, a political organizer and former collaborator of The Onion, who worked for a global activist organization called Avaaz.They became friends.

"I knew all those people who were doing activism and online organization, but if I was constantly reading blogs on new technologies, I knew no one.And Aaron knew all tech bloggers, ”recalls Wikler."We were both the entry ticket into the other world."

From Pacer to Jstor

Swartz's political commitment took advantage, and he attended online activist meetings organized by Wikler above Hong Kong Restaurant on Harvard Square.He began to make funny experiences with his sleep schedules, deciding that he would start to wake up at 5 am (the experience was short -lived).

He became a member of the Safra Center for Ethics of Harvard, studying the way in which money influences politics, the media and university and industrial research.And, on September 24, 2010, he bought an Acer laptop, brought him to MIT, and prepared to download documents from the JSTOR university publication database.

His project concerning the JSTOR differs from his escapades with Pacer in several titles.First of all, the JSTOR is not a reserve of non-semized government documents for copyright.

If its subscribers can access its content for free, this remains a paid service - large research institutions go as far as lengthening $ 50,000 per year to have access - keeping items of journals which for the most part are subject to the rights ofauthor.

Then Swartz was not pushed by a call for action and the release of information as easily identifiable as the incitement of Carl Malamud to Pacer.

There had been a previous potential: a few years earlier, he had collaborated with a Stanford law student called Shireen Barday on a project involving the download of almost 450,000 articles from the Westlaw database to analyze them to see who,Exactly, financed research in the field of law.

If it is possible that Swartz intended to post his jstor cache on the web, it is also plausible that he was only considering using the articles in the context of research as in the project with Shireen Barday.You can't have certainty.

Finally, Swartz seems to have tried to hide his link with the Downloads of the JSTOR - understandable decisions, given the interest of the FBI for his PACER project.This is probably the reason why, instead of simply using the Harvard network (where he would have had access to the JSTOR), he chooses to go.

Once there, he connected to the wireless network of the MIT as a guest and executed a script allowing him to recover a host of articles.If authorized users can theoretically download everything they want for free from the JSTOR, its conditions of use prohibit the use of programs encouraging mass download.

Swartz should know that his script was going to draw the JSTOR's attention and give birth to the suspicion that he wanted these articles for something other than his personal use.

The jstor blocks access to all the

He was not wrong.According to the government's indictment against Swartz, these "rapid and massive downloads and download requests hampered the capacity of the computers used by the JSTOR to provide articles to client research institutions".

The JSTOR detected a problem and blocked Swartz's IP address.The young man gave it another and started again.The JSTOR blocked a whole range of MIT IP addresses.Then he entered into contact with MIT, which undertook steps to prohibit Swartz's computer with access to his network.

The indictment says that Swartz succeeds in getting around their security devices and also obtained another computer, using both to download more JSTOR items.This would have had the consequence of crashing certain servers;In response, around October 9, 2010, the JSTOR blocked access to its database at all.

Around this time, Swartz stopped downloads for about a month, probably because he went to Washington D.C. with Wikler to participate, as a volunteer, in the preparation of the 2010 mid-term elections.

When he returned to Cambridge in November, he started downloading again.This time, he decided to anticipate any wireless IP ban by directly connecting his Acer cell to the MIT network.

A long tradition of openness and freedom ...

No doubt logically, MIT buildings are designated by numbers instead of names.Students take courses in building 3 (mechanical engineering) and take their meals in the W20 building (student center).

Building 16 is one of the least essential structures in the campus.It is a connector that contains the center of foreign language and literatures, the comparative medicine division and, in the basement, an electric and telephony wardrobe just behind a double door with a danger panel.

When Aaron Swartz entered the room 16-004T for the first time at the end of 2010, neither the building nor the wardrobe were locked, which was not unusual.MIT is one of the most open universities in the country.

Its flagship building, the majestic building 7, is still open to the public.From there, you can access almost all the spaces of the central campus without any problem by a network of labyrinthine corridors.

And students are not the only ones to come and come as they see fit.For years, local theater troops have used empty classrooms as a rehearsal space.

The MIT free access policy is a heritage of culture created by Richard Stallman and AI Lab.At the time when there were very few computers there, some teachers and administrators used to lock the rooms which sheltered the precious terminals.

Stallman and his Hackers counterparts, who believed that computers belonged to anyone worked on it, considered a locked door as a personal affront.As Steven Levy describes in Hackers describes, they gave themselves a lot of trouble to access the posts-forming locks, crawling in the false ceilings, going so far as to use the force to open a door.

Thirty years later, the MIT enthusiastically recovered the hacker's legend, selling the idea that innovation and progress should not know any barrier.This principle is an essential element of the culture of the university, and legendary "hacks" - sophisticated pranks going up to the 1860s - are celebrated on the MIT reception site and the pages of the former students.

The list of the best on the hacks.mit.edu site includes the time when, in 1994, students "changed inscriptions inside the lobby 7," established for the progress and development of science andFrom its applications to industry, arts and agriculture "in“ established for the progress and development of science and its applications to industry, arts, leisure and hacking. ””

... but a current "opening" far from the ideals of the hackers

But if the students of the MIT and the former students taste the image of carelessness of the school, it has been a long time since the university is no longer "open" in the way in which the pirates of Ai Lab heard it.Community convictions with a socialist tendency of the Stallman team are abominations for MIT, which is dedicated to a large extent to research for government and industrial groups.

The University's website prides itself on "appearing at the forefront of research and development and development expenses funded by the industry of all universities and grandes écoles without medical school".

Given its dependence on the government and the financing of companies, the MIT has every interest in appointing administrators capable of speaking this language.The school president at the time when Swartz Pirata Le Jstor was Susan Hockfield, a neuroscientist by training, willingly intransigent and who did not seem interested in the maintenance of the university's opening image.

“When you went on the second floor of the MIT, you passed in front of the president's office, and the door was closed;You passed in front of that of the vice-president, the door was open, "recalls Robert Swartz, the father of Aaron, who worked as a consultant for the media lab of the MIT:

MIT, less and less tolerant

Many sources suggest that, under the Hockfield, the university had become much less tolerant of incidents which, as harmless as they may, could potentially harm its image.In 2007, for example, a student named Star Simpson was arrested at Logan airport after safety officials took printed circuits on her sweater for a bomb.

Simpson did not think of badly, but the event could potentially harm the standing of MIT in the eyes of the public and the sector.The MIT published a press release criticizing Simpson's "irresponsible" acts, and did not offer her any kind of help during the legal tests she then had to undergo (Hockfield later expressed her regrets about the management of thesituation).

This was what was at the end of 2010: an institution which left its doors open, but which looked in the way anyone left the right path.

When the MIT police learned that someone had connected to the school's computer system, nothing surprising that she has set up a trap to catch the culprit.And he was not particularly surprising either that this culprit turns out to be Aaron Swartz.

On January 6, 2011 at 12:30 p.m., Aaron Swartz returned to the room 16-004T to recover the laptop and the external hard drive that he had hidden under a box.The place had already been put under surveillance.

Less than two hours later, said the Cambridge police report, an agent saw Swartz on his bike.The young man tried to escape the police by fleeing on foot, but he was quickly apprehended.

Six months later, he was charged by the federal state for downloading around 4.8 million items based on JSTOR data.In 2012, the charges chosen against him were weighed down, with 4 to 13 the number of charges.

A struggle from childhood for free information

Since childhood, Swartz has been working for free and open information.This was the promise of the semantic web and Creative Commons;This was philosophy at the heart of his work for Open Library and Pacer.It was obvious: it was necessary to facilitate the acquisition and study of data.

In 2008, he wrote the guerrilla manifesto for free access:

At the time, this text should not have moved the crowds.Swartz used to do in provocation by taking more or less seriously.

As a teenager, he wondered about the "absurd logic" of laws prohibiting the dissemination and possession of infantile pornography.In 2006, he believed that music became objectively better, and that Bach's well-tempered keyboard was perhaps lower than the 2005 album by Aimee Mann The Forgotten Arm.

But after the history of the JSTOR, the manifesto took on another magnitude.He was paid as proof by the accusation to demonstrate that Swartz intended to broadcast the downloaded items.

The public prosecutor considered that Swartz had "stolen a substantial part of the archives in which the JSTOR had invested [...] with the intention of [making them on one or more file sharing sites".What Swartz's family and friends unanimously contest.

The principal prosecutor, Stephen Heymann, was not one to show leniency.In 1997, he wrote an article entitled "Punish cybercrime" for the Harvard Journal on Legislation, in which he called Congress to tackle the unpublished challenges posed by delinquents of the digital era."The fact that computers can perform the same task as a human millions of times faster multiplied incredibly the capacity for nuisance of a single act," he wrote.

A "perfect" or "catch-all" law

Swartz was accused of having violated article 1030 of the American Federal Criminal Code, or Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1984 (he was also criticized for having violated articles 2, 981, 982, 1343 and 2461).In his 1997 publication, Heymann erected this CFAA as a model, calling it "perfect legislation against computer crime".

Not everyone is of this opinion.This law is "a notorious tote", recently noted Emily Bazelon in Slate.com:

In 2006, for example, a woman from the Missouri called Lori Drew persecuted her young neighbor on the Internet;The girl, Megan Meier, ended up committing suicide.Drew was charged with the federal level in the name of article 1030 for non-compliance with the conditions of use of mypace.

In an Amicus Curiae memory, the Electronic Frontier Foundation argued that, as dramatic as Meier's suicide, pursuing Drew under this charging chief did not make sense - it constituted "a dangerous dilation of the CFAA [...] which would make criminal proceedings liable to the daily behavior of millions of Internet users ”(Drew was finally found guilty of minor offense at the CFAA, but the verdict was canceled later).

Sopa and pipa, two unbearable bills

While he was struggling with justice, Aaron Swartz became interested in another anti-pirate law that web activists estimated unrealistic: Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA).As presented before the House of Representatives, this bill intended to strengthen the intellectual property right by allowing the legislator to close the sites (and possibly to stop their owners) which diffused in streaming or accommodated without authorization under Copyright.

Large media groups had been pressure for years for Congress to legislate on copyright attacks.The SOPA was the direct descendant of the online infringement and counterfeits Act ("bill against offenses and counterfeits on the Internet"), debated in the Senate in 2010, until Senator Ron Wyden gave him a commission fate.A revised bill was again submitted to the Senate in 2011, under the name of Protect IP Act or PIPA, twin legislation of the SOPA.

During its first presentation in October 2011, the SOPA was supported by large media groups and the American Chamber of Commerce.But web activists were quick to denounce what they considered an inept offensive, an attack on cyberculture which would suffocate all creativity, would promote large groups at the expense of small independents and would in fact condemn the free, open and open internetnon -commercial.

The Sopa and Pipa opposition movement was only waiting for Swartz.He embodied everything for which the young man worked and everything he believed in: reform of intellectual property law, collaborative culture, free access to data, political activism.Despite the proceedings started against him, or perhaps because of them, Swartz decided to go to the front.

Laws defeated thanks to Swartz

Before his arrest, the young man had stayed in Providence (Rhode Island) in order to participate in the electoral campaign of the young city councilor David Segal, who broke a seat in the congress.The election was lost, but Segal and Swartz, who became friends, created together asking for progress, in order to "promote progressive reforms for ordinary citizens, thanks to the organization and lobbying by the base".

Swartz made speeches, persuaded other organizations to enter the struggle and set out various tools to allow citizens to get in touch with the legislator and express their opposition to SOPA and PIPA.Faced with this gigantic wave of protest, the Congress had to backtrack in January 2012: the sopa and the pipa had lived.

Aaron Swartz during a gathering against Sopa and Pipa / Daniel J. Sieradski via Wikimedia Commons

Several people involved in the movement believe that, without the participation of Swartz, these laws may have passed.Holmes Wilson, whose Fight for the Future group has largely contributed to the blackout of Wikipedia and other renowned sites, thinks that Swartz and its organization have enlarged the range of diffusion of the anti-Sopa message:

A few months after this victory, Swartz intervened at a conference in Washington on the lessons to be learned from the anti-sopa.These bills had not said their last word, he warned:

If the victory against the sopa and the pipa was very real, the end of the protest campaign brought Swartz back to another reality.His friends had been assigned to justice.

And although the JSTOR would have given up prosecution, the government, with the tacit support of the MIT, did not let go."A flight is a flight," said the general prosecutor Carmen Ortiz in July 2011, "whether by means of a computer or a foot-standing, and whether they are documents,data or dollars ”.

Despite his attachment to Cambridge, Swartz felt that he had to leave.From mid-2011, he spent more time in New York, and it was at this time that he approached his friend Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman.

A activist who worked for Avaaz with Ben Wikler, Stinebrickner-Kauffman had met Swartz the previous year in Washington.They shared the same interests and a similar story ("we had fun with our somewhat confused situation," she says. "In the eyes of the census, we could have passed for two young singles having dropped thestudies and living together in a studio. ”)

Love was gradually infiltrating an accidental ground."The month when we started to go out together, he dropped two jobs, broke with his girlfriend, moved from Cambridge to New York and he was charged," continues Stinebrickner-Kauffman."It was a difficult time for him."

Alone against the system

They settled in New York, in a studio in Crown Heights, in Brooklyn.Once the battle is completed against the SOPA, the Jstor Aspira affair all the time and the energy of Swartz.

"At the start, when we were in New York, he took the bus to Boston every Monday to present himself in court at 9 am and prove that he had not fled," recalls Wikler.Swartz only discussed the case with his father and lawyers;He did not want his friends to be mixed with it, that other people are quoted to appear.

The pressure weighed only on him, and on Stinebrickner-Kauffman."He did not allow himself to count on others," she comments."But this strength was synonymous with solitude".

Being the last of the brave to fight against a corrupt world was an attractive perspective, especially for an idealist such as Swartz.However, this implied not to let his opponents see that he had reached.

"He wanted everything to seem normal," says Stinebrickner-Kauffman.This is why he continued, as he had always done, to engage in new projects, by becoming for example regular columnist for The Baffler, a freshly resurrected left publication.

"Aaron was the least pretentious person in the world," says John Summers, editor -in -chief of the Baffler."He was ready to chat for hours to put a paper magazine on foot."

Need money

However, Swartz no longer had the means to flutter.To make sure, he needed money.While Lawrence Lessig's wife, Bettina Neuefeind, set up a funding fund for her defense, he started, reluctantly, to ask their help from easy relations.

In August 2012, Jeff Mayersohn, owner of the independent bookstore Harvard Book Store, received an email from his friend.He agreed to contribute and suggested organizing meetings to raise more funds.Swartz refused."I already had trouble asking you," he justified himself.

Meanwhile, it became obvious that the public prosecutor's file was not very well put together.In the new indictment of September 12, 2012, he was criticized for Swartz for having "maneuvered to enter the Electric Wardrobe of the MIT".However, the door was not locked and had even remained open after the university and the authorities noticed that we entered there to try to access the school network.

The accusation also reproached Swartz for having "maneuvered in order to [...] access without authorization to the MIT network, by means of a switch located in this wardrobe" and "to access the archives of digitized articles of the JSTOR thanksto the MIT computer network ”.

However, Alex Stamos, an independent expert committed by the defense of Swartz, was ready to reply: according to him, Swartz had in fact had the tacit authorization to access the MIT network, given the laxity of the university in terms ofSafety-network.

In a post published on his blog after the death of Swartz, Stamos explained that the MIT computer network was extraordinarily porous - "in twelve years of security career, I have never seen such an open network" - and that thatIt was deliberate, because "in agreement with the philosophy of the university".

The JSTOR site, he continues, "did not even provide for the most basic control procedures to prevent what could be considered as a system violation, such as the requirement of a Captcha in the event of multiple downloads".

Swartz, insisted on indictment, had also "maneuvered for [...] that this access allows him to download a substantial part of the archives of the JSTOR to his computers and his hard drives" and to "bypass the measurements of the MIT and the JSTORaimed at preventing this massive copy, measures targeting users in general, and the illegal driving of Swartz in particular ”.

But then again, there is a matter of debate.Stamos advances as well as the prosecutors "failed to demonstrate that these downloads had led to any damage to the JSTOR or put it, except those attributable to the silly and excessive reaction consisting in blocking any access to the JSTOR, while the author of the downloadswas easily identifiable ”.

A confident lawyer ...

"We had a very good expert," comments Elliot Peters, Swartz's lawyer.“He had helped us understand the functioning of the MIT network and how to access the JSTOR.And it seemed to me that this access had not been unauthorized. ”

Swartz avait engagé Peters, associé du cabinet de San Francisco Keker & Van Nest, en octobre 2012. Peters, qui a également représenté Lance Armstrong, était le troisième avocat de Swartz.

Over the weeks, he believed more and more about the chances of his client and intended to breach a number of pieces of conviction that prosecutors counted to use during the trial."We have submitted several requests for abolition [of convictions], including one concerning the search for the laptop and the USB key of Aaron, because they took 34 days to produce the search warrant after theseizure, ”he said.

On December 14, Peters and prosecutor Stephen Heymann were heard by J. Nathaniel Mr. Gorton, who set a hearing of witnesses for January 25, 2013. A few days later, the prosecutors gave 170 megaoctes of new parts to conviction, who did notRendianet lawyers from Swartz than more optimistic.

There was indeed the trace of contacts between Heymann and the police prior to the arrest of Swartz.Peters was certain that this new deal strengthened the position of the defense.

On January 9, 2013, Peters called Heymann to discuss the upcoming hearing.Peters remembers:

... but an inevitable trial

But the prosecutor went there from the same old refrain: the public prosecutor would in no case accept an arrangement which does not include imprisonment, and if there were trial and that Swartz was condemned, he would require seven years.

As usual, defense and accusation did not find common ground.The proceedings were therefore to lead to a trial, to start on April 1 except other postponement.

On January 10, the day after this last failure to reach an agreement, Stinebrickner-Kauffman returned to New York after a stay in the countryside.Swartz sent her an SMS asking her at what time she was coming back, without explaining to him why.When he arrived, he jumped from behind the door shouting "surprise!"

Stinebrickner-Kauffman was tired, but Swartz, very fit, insisted that they go to find friends at the Spitzer’s Corner, a bistro from the Lower East Side.Swartz has granted two of his favorite dishes: cheese macaronis and cheese toast.

The pasta was passable, but Swartz and Stinebrickner-Kauffman found that the toasts were among the best they have ever eaten.

A call in the car

On the morning of January 11, a week after he said that the year would be beautiful, Swartz woke up depressed --Stinebrickner-Kauffman had never seen him so slaughtered."I tried everything to shoot it from the bed," she recalls."I put music, I opened the windows, I made her tickle."

When he ended up getting up and dressing, Stinebrickner-Kauffman believed that he was going to accompany him in the office.But Swartz said he preferred to stay at home to rest.He needed to be alone."I asked him why he had dressed," continues Stinebrickner-Kauffman."But he did not respond."

That afternoon, Peters studied the documents given by the accusation at the end of December.As his reading progressed, he became more and more optimistic for the hearing of January 25.

"If the request had been granted to us and the results of their search had not been paid to the file, they would not have been much for the trial," he said today."I tumbled into the corridor, shouting" Look at me! "»»

Peters put the files in his case and took his car.During the journey, he received a call from Bob Swartz.Aaron had committed suicide.

Swartz has been hanged over a month, and the initial shock has turned into something more acute."I'm so much more angry since his death," said Wikler.

He is not the only one.The family, friends and supporters of Swartz almost all say that they did not expect their suicide at all.They do not think that Swartz was depressed in the medical sense of the term - he was lunatic and sometimes excessive, but not depressed.

“I inquired about the depression and the disorders that accompany it.I studied the symptoms, and before the last 24 hours of his life, Aaron presented none, "wrote Stinebrickner-Kauffman on his blog on February 4.

"Depression is like ink that tints everything, which makes all black and impenetrable," writes Wikler."And Aaron was not like that.It was an almost entirely transparent being. ”

Relatives of Swartz also agree to show the finger at the officials of his suicide."The government and the MIT killed my son," said Robert Swartz during Aaron's funeral.

Lawrence Lessig - who had written in 2011 that the acts alleged against Aaron, if they were proven, were "criticizable on the ethical level" - estimated that the young man had been "pushed by what ahonest society could only qualify as harassment ”.

And now?

The truth is certainly more complex.The circumstances of Swartz's life are resisting any simplification, and the same goes for his death.Anyway, if Swartz supporters believe they understand his fatal gesture, it is more difficult for them to answer another question unanimously: and now?

Funeral ceremonies and innumerable online orals have proposed as many avenues to honor the memory of Swartz with dignity: Computer of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, Easy Access to University Sources, use of public archives regulations to give free access to documentsof State.

For its part, the Anonymous collective hacked the MIT site on the night of January 13 and short-circuited the university network by means of a denial of service to publish a list of "wishes", among whichappear: "reform of cybercrime laws", "reform of intellectual property laws and copyright" and "reinforced and resolved commitment for a free internet, without hindrance or censorship, which guarantees all equal access and'stock".

(MIT is conducting an internal investigation into his role in the Swartz case. The man leading the investigation, Professor Hal A Abelson, is one of the main founders of Creative Commons and he sits on the Council of theFree Software Foundation by Richard Stallman.)

You have to expect Swartz's inheritance to debate, and maybe you have to rejoice.Swartz was acting in agreement with his convictions and pushed his entourage to do the same.But how can we agree on the continuation to give to the mission it had set for itself, when it married so numerous and varied shapes?

What remains of Aaron Swartz?

"There is an old joke between programmers on the future reserved for a code from which the author dies overthrown by a truck," wrote Swartz in 2002, in a post detailing what should be done with his work if heDied unexpectedly.He wanted his code to continue to be improved and that he remains open, in tribute to the fights of his life and to what he would leave behind.

In the end, what does Aaron Swartz leave?Half of the sites he created in his childhood are no longer.Or rather, these are ghosts that wander somewhere in the internet archive of Brewster Kahle.

Network info is no longer.The fan wars fan club from Chicago Force has changed its site.RSS 1.0 was quickly overshadowed by its rival on RSS 2.0.And both were dethroned by the new Atom format.

Infogami was a failure.Jottit too.Reddit was only successful for many years after the departure of Swartz.Watchdog.net has not been refined.The semantic web has never really taken.

What is he accomplished, this universal, hyperactive and lunatic scientist, who has not finished half of what he had undertaken?Swartz has been successful, of course.His action was decisive to put a brake on the sopa, and Creative Commons as well as Demand Progress remain the emanation of his unalterable belief in access and a free internet.

But more often than not, Swartz had to count with failure.Solving simple problems did not interest him.He wanted to structure the world, while the world is chaotic;He wanted to reform the systems, but was depressed when, despite his repeated attempts, the systems resisted.

"I remember having discussed collaborations that had not worked with him," says his friend Nathan Woodhull.“I believe that in fact, people were not up to their expectations.He knew what he wanted to arrive, and we didn't situate ourselves. ”

There would be more people like Aaron Swartz if our schools, businesses and governments were configured to produce more Aaron Swartz - they were flexible, reactive and adapted to each, if they encouraged collaboration and theA spirit of initiative, if they encouraged to fully live his passions and ideas.

But major systems are not like that.The idealists will always be the minority, the one that does everything to perfect a world that will never be perfect.

His idealism spreads

In the 1980s, Richard Stallman saw his friends letting go of their ideals to make money with proprietary codes.He chose a different path by founding the Free Software Foundation and acting according to his principles, he chose the path of resistance.

What does Stallman accomplish?Not much, if we stop to the fact that the majority continue to use Windows and Mac OS.

But he inspired Lawrence Lessig and an early child named Aaron Swartz, who had a member card of the Free Software Foundation, housed on his site the PDF of a collection of tests from Stallman, and which declared, after having listened to theResearcher at a conference that it was the type of man he saw himself becoming.

In the month following his death, Swartz's idealism began to spread.Internet facilitates activism - it only takes a second to retweet a petition.

Swartz was more demanding, he wanted a world where everyone would order their lives according to their convictions, not according to what is most profitable.Shortly after his disappearance, his friends created a site in his memory where who wants to leave a message on his life and his work.

The comments of his loved ones are much less numerous than those of perfect foreigners, of people from around the world who had never met Swartz, and who had never even heard of him before his death.

"What a misfortune that a being so brilliant and passionate [die] so tragic," wrote a certain Jason in a brief and sincere praise entitled "You have to change things":

When he lived in the Massachusetts, Swartz participated each year in the Mystery Hunt of Mit, a race for the puzzles of a weekend.Exactly a week after his death, the first day of the Mystery Hunt 2013, his former team organized a tasting of ice in his memory.

A large banner was spread out on the table, on which friends and admirers could write little words: funny memories, messages of condolence, etc.At the end of the evening, a slender boy dressed in a sweatshirt, who looked too young to be there, approached the table.To the marker, he simply wrote: "We will continue."

Justin Peters

Translated by Bérengère Viennot and Chloé Leleu

[1] Collective translation from the Framablog site (NDT).Back to the article.

Tags:

Tags: Prev

Prev